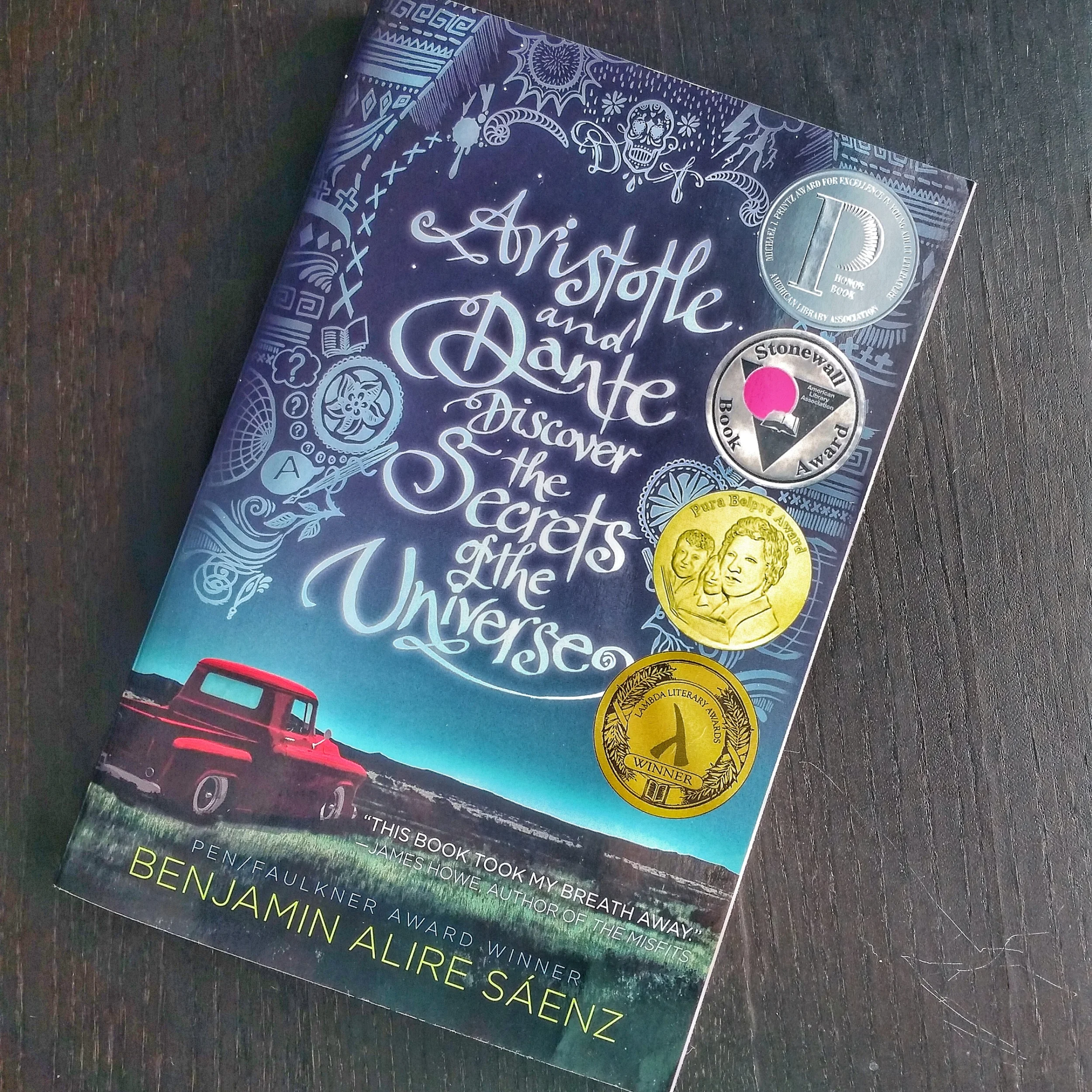

aristotle and dante

So, hooray! This is another Young Adult novel I've read. Published by Simon & Schuster BFYR (Book For Young Readers) and aimed at audiences ages 12 and up. Thank you, Back Flap, for all of that helpful information.

I'm starting to think that the Young Adult genre has more to do with how the book is written than what the book is about. Because, damn, this book dealt with some heavy stuff.

Set in 1987, this book hits notes on family relationships and secrets, self-discovery, hate crimes, cultural identity, and identifying the nature of the love you feel for someone (whether platonic, romantic, or something altogether different). It's intense in its sparse narrative, written in the first person point of view with an emotionally frustrated and (arguably) stunted narrator, and leaves the reader feeling both equally frustrated yet compassionate towards the characters.

I picked this title off a random list I found on tumblr. Something along the lines of "My Top (x) Favorite LBGT+ YA Titles!"

Outside of a few choice fanfiction, I haven't read or found anything that depicts an LBGT+ story without loads of angst and pain and, ultimately, a really really sad ending, which raises questions and a discussion about representation in media and a whole slew of other issues. But that's for another post. This, however, caught my attention (I'm looking at you, philosophy minor), so I ordered a copy and dug in a day or so after its arrival on my doorstep.

To dive straight into what this novel did right, I'll list off a few things.

The protagonists, Aristotle and Dante, are Mexican-Americans, so I was thrilled to have POC characters as the focus here instead of a token mention. They both deal with ideas of whether they're "properly" Mexican, and what it means to honor and express a familial culture while existing in the larger, more predominant, 'American' culture--whatever those terms mean to an individual at any given time. They both struggle with it, but because the reader experiences the story through Aristotle's (hereinafter referred to as 'Ari') point of view, the struggle is more poignant, and the associated expectations are more oppressive. The reader suffocates right alongside Ari, and it's only Dante's appearance that gives either of them--Ari or the reader-- a chance to breathe.

This disparity in feeling, this idea that Ari feels these pressures more acutely than Dante, could be attributed to the socio-economic and educational disparity between their families. Dante comes from a home where education is pushed and prided, where Dante is an only child and the focus of all of his parents' attention, and where both parents are highly educated and fairly well-off. Ari, on the other hand, comes from a home where education is important, but Ari's a trouble-maker. His father is distant, still stuck in his service during the Vietnam war, his older brother is absent, and his mother is trying desperately to somehow keep their shattered family together.

There's a craft issue in this novel that's done really really well that I have to mention: odd/unique names. One of the first things I was told in my Intro to Creative Writing class was, "never give your character a strange or unique name unless it is somehow relevant to the plot or character development. Don't name your protagonist Buttercup in, say, today's society without addressing the strangeness of her name and having it impact her somehow. Maybe her parents were hippies, and she hates it. Maybe she gets teased. But make sure you acknowledge that this name is strange and show how it effects her."

This novel's POV protagonist is Aristotle. And several several times throughout the book, he makes mention of how he's named after a family member, but how its also the name of a great philosopher. But he doesn't think of himself as that great, and he hates his full name because he doesn't feel like he lives up to it. So he goes by Ari. And most people call him that--because it's easier than explaining where Aristotle comes from, or dealing with the consequent teasing.

Then there's Dante. And it's mentioned once, in passing, why his parents named him that, and the explanation comes from Dante's father. Yes, it was from the beloved writer-self-insert The Divine Comedy. Ari's interiority addresses the strangeness of the name, too, but Ari, being the laid-back dude that he is, just accepts it as another incarnation of Dante's strangeness. He falls back on the notion of "Dante is Dante" often, and is remarkably free of judgement when he does so.

The titles ties these aspects together: Aristotle (not just Ari, but whatever the name Aristotle invokes in the psyche) and Dante (not just Dante, but whatever the name Dante invokes in the psyche) Discover the Secrets of the Universe.

Ari is in search of The Secrets of the Universe throughout the novel, and uses it as an overarching term for the complexities of life he can't understand as a teenager, how his mother and father must know them, because they know things he doesn't, and understand things he doesn't. "You'll understand when you're older," is a phrase that's thrown around a lot in this book, and Ari's position is, "Well, I'm nearly a man and I still don't understand it. When will I understand it? Will I ever understand it?" Is wisdom something that happens miraculously when someone turns eighteen? How are you one moment a child, and with the passing of a birthday, suddenly an adult? It's big and overwhelming and nearly insurmountable for him alone. Ari, as his name suggests, is the philosopher asking the tough questions about life, and acknowledges his ignorance in the face of the universe's vastness.

Dante doesn't seem to be in search of anything, not the way Ari is. Dante wants to live life. He wants to love. He wants to experience everything existence has to offer. Like Dante in The Divine Comedy, he isn't interested in the great beyond. (And I say this because, let's be honest, Dante goes for a wild ride with Virgil in The Divine Comedy, but isn't in the driver's seat of the experience. It's more like a safari ride at a theme park, where Virgil just explains what Dante is witnessing.) He's interested in what's in front of him, what he witnesses, and he's happy to accept the guidance of those around him while he makes his way through his own Inferno, Purgatorio, and, ultimately, Paradiso.

And yeah, they eventually reach their own Paradiso, and their adventure of self-discovery could be likened to the three parts of The Divine Comedy, but I'm not here to write a thesis; I'm here to say why this book is or isn't worth reading.

It is totally worth reading.

It hit so many of the right notes for me to highly recommend it.

- POC characters who are developed and complex

- LBGT+ characters who are developed and complex

- exploring various incarnations of love

- family heritage and its expressions that are developed and complex

- a rare gem in its time period (the late 80's were rough for minorities, okay, let's be real about that)

- organic development in ALL ASPECTS of the protagonist's life

The book pokes fun at itself and its subject matter the way a teenager would. The book dismisses the significance of certain events the way a teenager would. The book eventually comes around and realizes what it's been alluding to all along the way a teenager does. Everything about it is just so authentic and true on so many of its various levels, I can't not speak highly enough about this book.

THIS was what I was hoping for with Shiver. THIS was what I've been aching to discover about the popularity of this genre and why it means what it means to people. Yes, this book is aimed a young adults, but the problems Ari and Dante face aren't just faced by teenagers. The questions asked aren't always answered once adulthood is reached. And while Ari and Dante might have discovered the Secrets of the Universe in a way that satisfies them, there are so many people in the world who are still looking, who are still trying to make sense of it all.

This is a story that can speak to everyone. This is a story that takes the complexities of insecurities some don't have the courage to name and breaks them down into easily digestible parts for a developing mind. In so many ways, we're all still children, and one of the biggest take-aways from this novel is the comfort that you are not alone in what you think, in what you feel, in how you love.