This really should have been one of the first books I reviewed here. I really should have been, and I feel terrible it wasn't for several reasons:

- The author is based in my hometown area, teaches creative writing at my alma mater's rival, and has successfully taken a career path I sort of find myself on (got his degree in psychology, then went on to study creative writing).

- I read and studied this collection of short stories as part of my creative writing undergrad under the tutelage of one of my most admired mentors (even if he maybe doesn't know it).

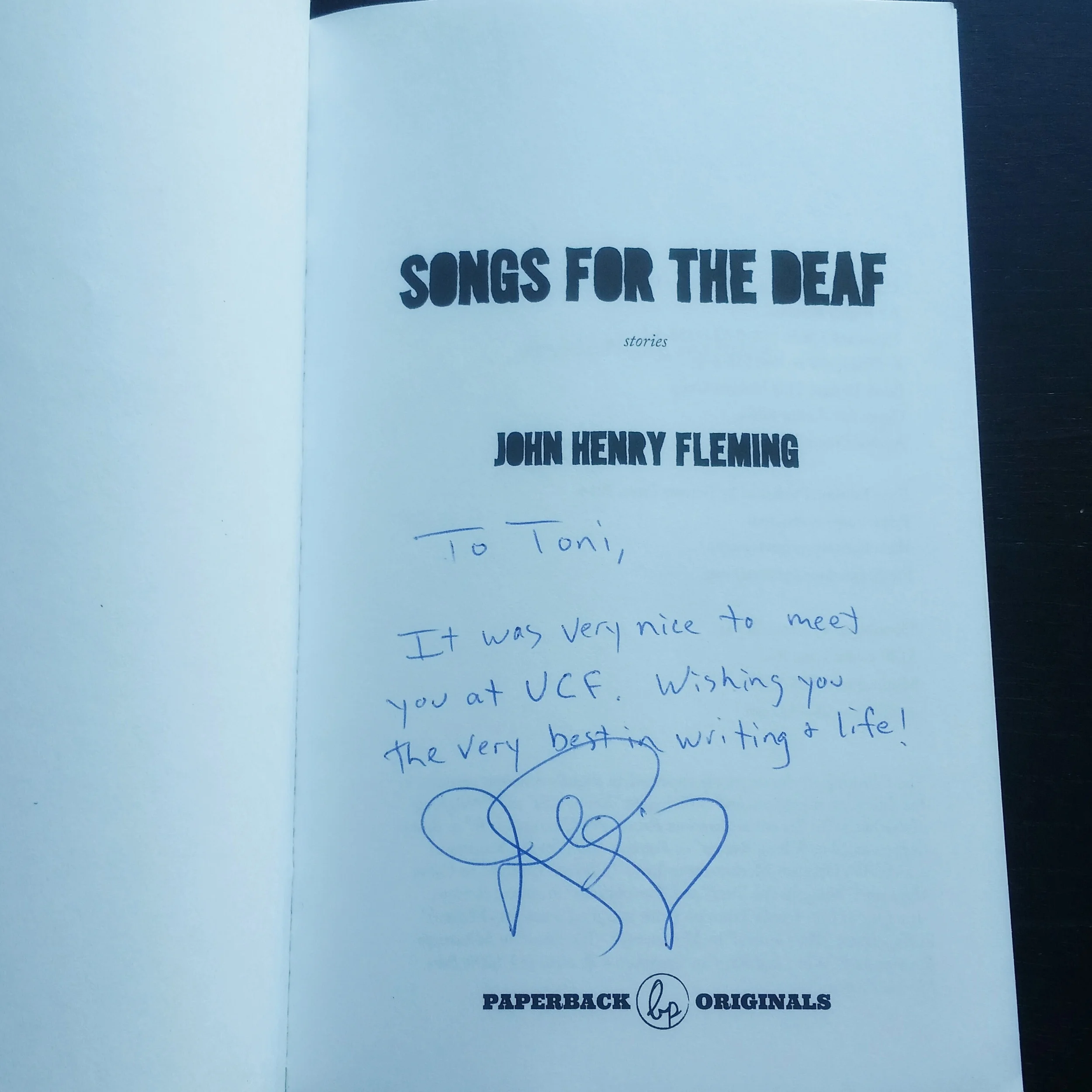

- I've met the author. HE SIGNED MY BOOK AND WAS SUPER NICE AND SUPPORTIVE AND REALLY ENTHUSIASTIC ABOUT WRITING.

- The publisher--Burrow Press--is a non-profit independent publisher from my hometown. They're a huge supporter of local talent, and I've met so many amazing, wonderful, and skilled people through their events, including, but not limited to, their staff and their published authors.

I should have reviewed this book sooner. I read this book two years ago. TWO. YEARS. AGO. I needed a refresher, so I pulled it out from my 'academic reading box'--yes, I have one of those--and flipped through it.

It was such a refreshing and nostalgic experience. I even went through my hard drives and found the assignments I'd completed relating to this book. You can find those at the end of the review post.

When I finished my undergrad, I had been exposed to so extensively to short stories, I had basically unlearned the necessary discipline to not only read something longer, but to write something longer. Every display of my craft understanding was a short story. Every time a craft element needed to be studied was through a short story. Basically, I suffered from a literary equivalent to television programming--switch your attention too often, and you find you can't really pay attention to anything longer. I described short story collections as one-night stands with characters. I didn't need to spend dozens of chapters to become invested in a character--a short story does this with a handful of sentences. I didn't need to spend hours to learn their fates--a short story wraps this up, again, in a handful of sentences. Short stories, by their nature, have to straddle and master a language balance of density and economy; there are only so many pages, so many words within the term 'short story' to establish and develop a story and its characters.

It's hard to do. And then to do it over and over without repeating yourself is even harder. Thankfully, I had a lot of exposure to really talented and well-written author collections. My professor wasn't mistaken in assigning Songs for the Deaf.

Here, Fleming plays with ideas of God (Christ figures, specifically), misattributed causes for effects, and the conditional obligation people have to morality. He blurs the line between what is considered acceptable, and what is unacceptable with the obstacles his characters face--I think this is especially true in Chomolungma. He uses humor, like in The Day of Our Lord's Triumph (with Marginal Notes for Children), where there really are marginal notes; and the absurd, like in Xenophilia where, well...break the word down and you'll understand. There are also examples of various stylistic choices, like in Cloud Reader, where there is an absence of quotations marks a la Cormic McCarthy and single dots used to separate sections. In Xenophilia, the sections are numbered. And in Chomolungma, sections begin with a single bolded phrase, setting the location.

Altogether, the collection was used as a teaching tool for my undergraduate course, and it can be used as such for any writer or reader. Songs for the Deaf offers a vast array of structures and styles, none of which detract or distract from the gravity of the world we delve in to, however deeply or briefly we do so. It's quite the opposite, in fact. These variations in structure lend themselves specifically to each story. In A History of War in Three Parts, each part is differentiated from the others by a heading, which serves as a primer for the proceeding text, as well as a relational point between the three parts.

Can you tell I actually studied this collection at university, yet?

One thing I can say, without a doubt, is that I enjoyed every piece of material I was directed or required to consume during my university education. It might have been for an assignment or a grade, but these circumstances didn't lessen the excitement of experiencing something new. And, well, there's nothing quite like becoming so familiar with a work, and then meeting the author in a casual, no-pressure setting.

I loved Songs for the Deaf. The order in which the stories are presented paces the reader without exhausting them and entices curiosity without trying too hard. The works themselves--their styles, structures, voices, language--vary enough to avoid feeling repetitive, but become familiar enough to recognize Fleming on the page.

Lucky me, I can recognize Fleming most acutely on the title page. :D

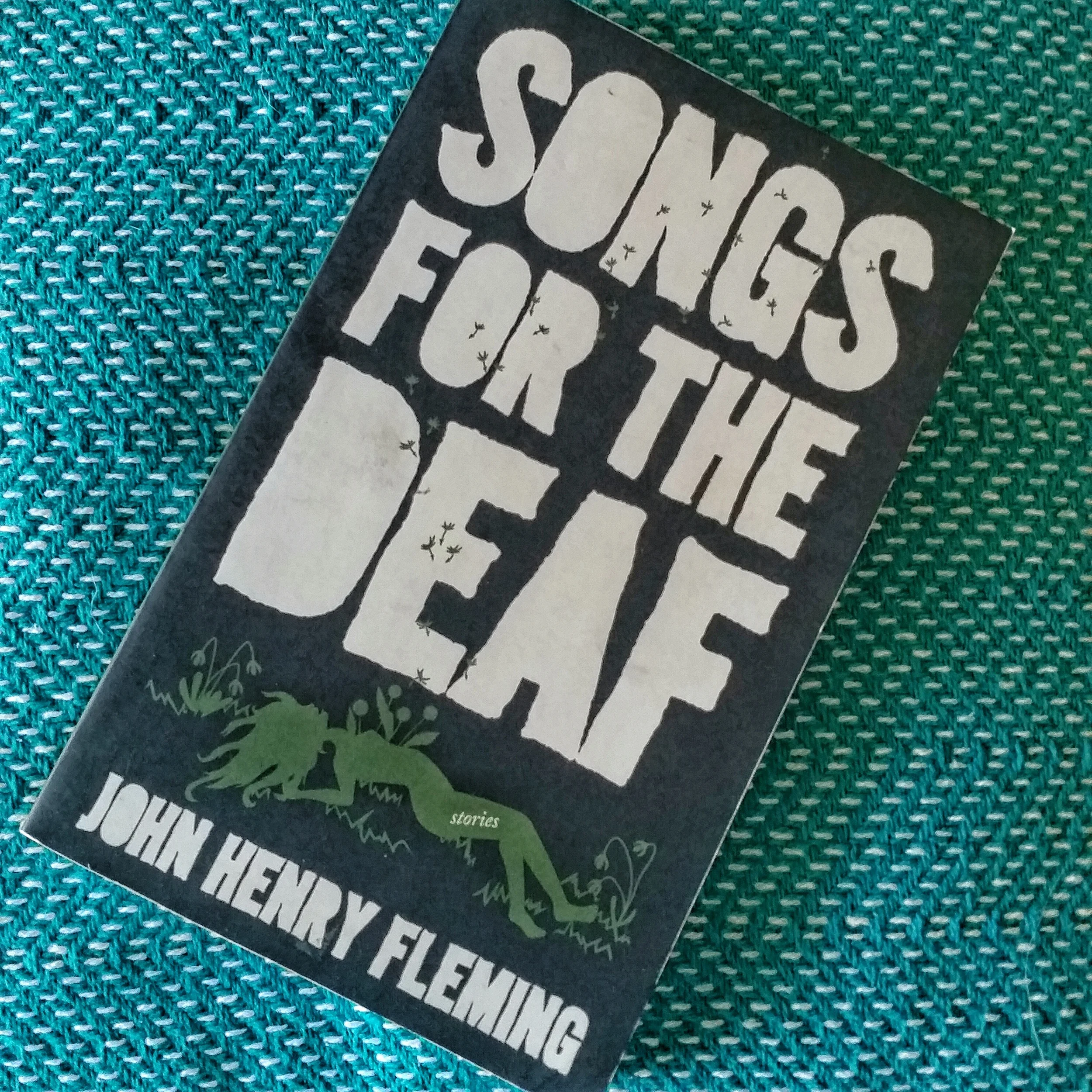

So you don't get Fleming's Songs for the Deaf confused with similar titles, or the Queens of the Stone Age album, here are links to get your copy:

Burrow Press | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Books-A-Million

Be sure to check out Dr. Fleming's website for updates on his new novel, The Prince of Foul Weather, and his other published works.

John Henry Fleming's website | Burrow Press' website

And for those of you interested, as promised, my HOMEWORK circa Spring 2014:

In "Cloud Reader" and "The Day of Our Lord's Triumph," Fleming seems interested in Christ figures. Does he use these to good, bad, or blasphemous effect?

I feel it’s difficult to judge whether the effect was simple good, or simply bad, or simply blasphemous. What I think he does is, instead, point to the psychological need for answers. In Cloud Reader, it’s alluded to that conviction alone is what makes the Cloud Reader credible, that he stared at the patterns of clouds and decided that there had to be some sort of meaning behind it. This is a natural form of human curiosity. In The Day of Our Lord’s Triumph, Fleming frames a basketball game between a bunch of kids in a religious fashion, language and marginal notes “for children” making clear the following based on this story that—as reader’s today—we see for what it truly is. It casts an interesting and critical light on the significance of religious texts as a whole, I think, but not necessarily in a blasphemous way (then again, I have no religious affiliation, so what does not offend me may offend others). Fleming makes it clear that meaning is not inherent in our experiences or in our realities; meaning is something a person injects and imposes upon their experiences and the reality they live.

Which of these five stories was your favorite? Least favorite? Why?

My favorite by far was Cloud Reader. I absolutely loved the McCarthy-esque style, and loved the, what I thought, was the slow and steady reveal of the narrative. I also loved the focus on conviction and how it means different things for different people, and how it manifests differently in the mind based on the surrounding culture. It was a piece that made me think, and spoke to my philosopher’s heart. I just absolutely loved it.

My least favorite would be Weighing of the Heart, but this is only in relation to the group of stories we’ve read—it enjoyed it on its own, but comparatively, I liked it least. I disliked the use of the first-person when compared to the third-person in the other pieces. I felt the piece was far less economic in its language than the other pieces, and seemed forced in its poignancy, where the other pieces just read as naturally powerful, in some form or fashion. It was also a story I felt I had to force myself to read, just because the flow seemed comparatively disrupted. (Maybe this is an “order matters” sort of thing with a collection of stories? I’m not entirely sure…)

If you were going to summit Everest, would you get the discount Sherpas, or would you spring for the real Sherpas?

Um, of course I would spring for the real deal, if for no other reason that I haven’t the faintest idea how to climb a mountain and wouldn’t trust published material as much as local knowledge. As if Chomolungma wasn’t enough of a warning for the folly of discount Sherpas, my own fears and self-doubt would be enough to determine that the extra cash would be worth the peace of mind.

And can we just take a second to talk about the abruptness of the deaths in this piece? I mean, I literally had to go back and reread those paragraphs because I couldn’t quite believe that I’d read and how much it felt like punch in the face when I read it. And then how Father and William just…carry on...? It was definitely as “WTF” moment for me.

What is the significance of the repeated imagery of the whistle in the title story?

To me, it was a physical reminder of why Jeremy resented Tony so much. The entire town was so preoccupied with his angelic voice that no one paid heed to something as serious as a sudden and tragic death. Jeremy keeps the whistle to remind himself not to get swept away in the hubbub and overrated admiration of Tony. He carries it for years and years, and it keeps him grounded, immune to the mass worship, much the way Marietta’s deafness keeps her immune as well. In the end, Jeremy gets the one thing Tony can’t get—Marietta’s attention. But Tony is so self-absorbed that he believes his voice to be the miracle sound that reaches beyond deafness. Jeremy, however, is not so self-centered, though he does appreciate when Marietta says it was his whistle that roused her that fateful night. It characterizes all three of the characters—Jeremy, Tony and Marietta—with this one acknowledgement, and sums the piece wonderfully.