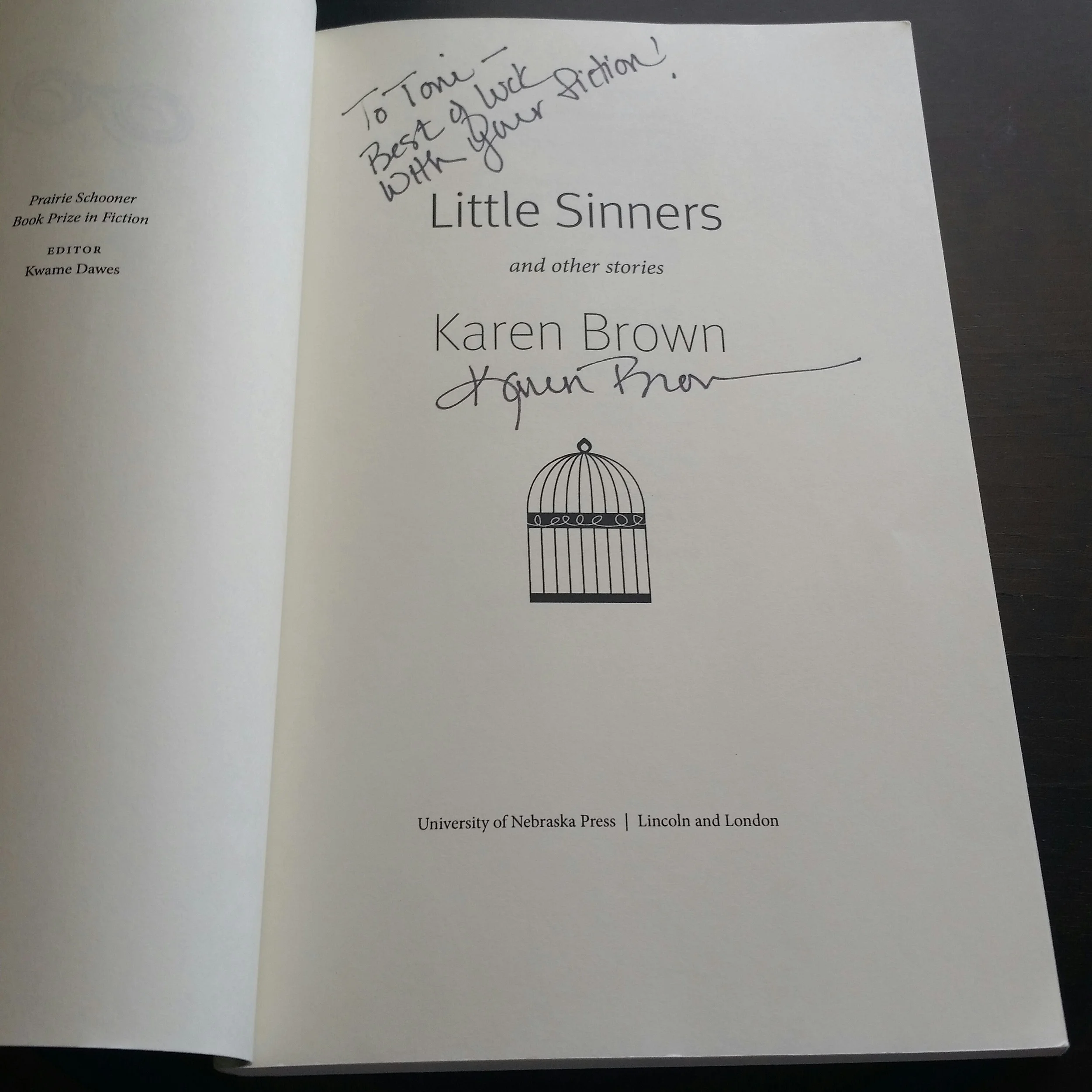

little sinners

Alright! Hello and welcome to the christening post of THE NEW WEBSITE. :pops some Santana Champ 'cause it's so crisp: HEY-OHH!

Fun Fact #1: Little Sinners is published by University of Nebraska Press! They were featured at the Denver Publishing Institute I attended, and I might get an MFA from the University of Nebraska. :cheers:

Fun Fact #2: Dr. Brown teaches at my alma mater's rival, just like Dr. Fleming. I was surrounded by such talent and skill in my hometown.

So, this is another short story collection I studied at length in my undergrad. And just like Songs for the Deaf, I really should have reviewed this book sooner. Part of me is glad I've waited--especially with Little Sinners--because I feel I've learned and grown a lot within the last two years. I feel I can appreciate this collection much more, now.

And boy, do I. Damn. (I'm a little ashamed of my, like, attitude in my homework, if only because I feel like my ignorance is really really apparent there, and that's embarrassing.)

The first thing about this collection I'd like to point out is how pivotal it is, by its very nature: it's a collection of women's stories written by a woman. While it undoubtedly includes characters that are men, the protagonists are (arguably) all women. I know there are plenty of examples of this that exist, but they're rarely easily accessible. To find the literary works of women, you have to study it specifically, seek it out specifically. It's just not an integrated part of general study (unfortunately). And here I am in an Advanced Fiction Workshop getting tossed this awesome collection because of its craft merits. A+ to my professor for diversity in material!

Another interesting aspect of this collection is its overall presentation and structure. According to a few of my professors, short story collections usually start and end with strong pieces, with the title piece closing the collection. Little Sinners deviates from this formula by placing its title piece in the fore, setting the tone for the entire collection in two ways.

The first, through the title's invocation of the term "little sinners." Little--referring to what? Relative to what? The degree of the sins committed, within society, within the characters themselves? The position of the sinner to relationships, to society? The sinners' ages? And then we have Sinners. Well, sin--crimes against moral or holy law, the highest of trespasses against God. But do these characters sin, really? Is what they do truly so highly reprehensible? Brown gives compelling, dimensional evidence both for and against, but never lacks compassion for her characters.

The second tone-set comes from the title story itself--Little Sinners (I write about this in my homework, so you can check there for a text-supported argument) . It's an epistle--a letter. A letter written to--you? Another person/character? This technique, as I conclude in my homework analysis, almost automatically humanizes the letter's author. Regardless of their crimes, or in this case sins, they are human, and thus, flawed and complex. While a reader may not be able to condone their actions, they certainly have a hard time completely condemning them, too. It's such a fucking brilliant authorial choice--it's a single stylistic structure that, by its very nature, translates Brown's compassion to the reader. It grants her room to explore the characters in ways otherwise prohibited. After reading Little Sinners, after becoming a more understanding reader, you read the rest of the collection primed to exercise that same understanding with each new character introduced.

This is why I'm happy to review this collection now, two years after initially reading it in class. I wasn't able to exercise compassion two years ago.

In fact, I remember, distinctly, an embarrassing interaction between myself and a professor I'd later study under:

"Your protagonist is a super douche, but you don't seem like a douche yourself. You seem pretty damn nice. So how'd you write such a terrible guy? And how'd you get me to root for him in the end?"

Apparently, he gets asked this question a lot, and his answer always remains the same: compassion.

I'm embarrassed by the bullheadedness of my past self, of the sheer level of internalized misogyny I had neither recognized, nor worked through at the time. It prevented me from identifying and truly appreciating the brilliance of Brown's work (you'll see it in my homework answers) until two years later.

I don't feel I can make an accurate judgement call on Little Sinners' themes, which are infidelity and marital faithfulness.

On the one hand, it can be argued Brown limits the scope of her women character's stories to their romantic and sexual relationships with men; and how their behavior in those relationships effects their experiences within society (both society as a direct external environment and force, and the society they perceive through their own paradigms and learned experiences). This paints women in an unfavorable light: the temptress, the gold-digger, the deceiver. There are, obviously, women who ascribe to these characteristics, but these are also the archetypes women are boxed into by the people who hate them.

On the other hand, it can be just as thoroughly argued that Brown has taken this 'typical narrative about women'--the unfaithful wife--and flipped it on its head. Each woman protagonist has her own complex web of reasons that lead her to infidelity. Not only is each woman fleshed out into a fully dimensional character, the protagonist's similar and sometimes shared experiences could also show Brown writing within a real-world system that forces similar experiences upon them. Basically, women are relegated to a particular set of circumstances which, ultimately, lead to a particular set of similar results. But even within these seemingly limited confines, Brown introduces an array of complex and interesting women, many of whom just happen to have unfulfilling marriages.

I enjoy and appreciate Little Sinners much more now than I did upon my first read-through; and I would recommend it, really, to anyone. Short stories are a particular taste; so are topics. But there's something about good fucking writing that, I think, transcends both of those things. Brown is simply fantastic.

You can get your copy of Little Sinners by clicking any of the links below. And feel free to come discuss its topics and techniques with me in the comments section!

University of Nebraska Press | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Books-A-Million

Little Sinners is one of two published short story collections by Karen Brown. The other is Pins and Needles. She also has one novel published, The Longings of Wayward Girls. Follow her website for news and updates on her latest novel, The Clairvoyants, and her other published works.

Karen Brown's website | University of Nebraska Press' website

For those of you who've stuck around, here's my embarrassing HOMEWORK from when I studied this collection circa Spring 2014.

SPOILERS AHOY!

In addressing the story to "you," the story "Little Sinners" becomes epistolary, a story told as a letter or address to another person. Why might Brown have chosen this style, and do you feel it made the story more effecting? If so, how? If not, why not?

There’s something about a confession that automatically tugs at the reader’s heartstrings. Maybe it’s the presumed assumption of guilt or remorse, or the presumed honesty—because why would one ‘confess’ unless it was the truth and there was regret for the deed?—but the entire tone of the piece assumes responsibility of what transpires. From the title, to the innocence with which the addressee of the piece is described, to the very last line “Just this acknowledgement, whatever it is worth, of all the little deaths that came before it” (15), there’s an acknowledgement of wrongdoing. The language describes rather brutally the power variance between the narrator and Francie: the narrator describes her as “the weird neighborhood girl” (2); Val snatches the change purse from Francie’s purse (3); the brutal rejection when Francie inquires about who the narrator and Val are meeting by the creek (4). All of it places the girls above Francie, then describes how they take advantage of Francie’s need to be accepted. The narrator offers a reflective explanation espfor the prank of, “I wanted it myself” (6). But by using an address directly to the victim of her cruelty, the author automatically summons the sympathies and compassion of the reader, loads the language with retrospective remorse, and immediately creates an emotional link between the reader and the characters. I feel it was an effective strategy. It, personally, forced me to withhold judgment and see the perpetrators of such meanness as human before I was even aware of the ramifications of the crime.

"Stillborn" makes use of roving 3rd person limited omniscient point of view. We move between Diana's head and Ava's head. Why do you think the author made this choice? Was it the right choice?

I think the author decided on this method to show how this story belongs to both women in almost equal measure, and to give a sense of the cyclical nature of life, fate, the universe, what have you. Diana’s story is eerily similar to Ava’s, and Ava’s involvement in Diana’s story is a sort of cruel irony that does not escape Ava. Diana knows her husband is cheating on her, Ava was mistress to the father of her child. By getting into the head of each woman, the reader is privy to this connection between them, this almost-mirroring of their lives. But because the women never speak of these details, they don’t realize how much in common they truly have. And that’s the most interesting aspect of the piece.

Karen Brown returns again and again to the subject/theme of faithfulness and marital infidelity. What might she be driving at in these stories? Does the adultery motif deepen with each story, or does it become redundant, in your opinion?

While I personally found the adultery motif particularly worn out in the last set of stories (at which point I realized the bulk of the book’s weight relied on this theme), the way she presents each set of circumstances is different, and it reflects the actuality of relationships and the motivations of adultery. People cheat for different specific reasons, but almost all of them can be grouped under an umbrella concept of unfulfillment. In some form or fashion, the adulterers are unfulfilled by their partners and thus cheat. Through cheating, the adulterer learns something about themselves, their relationship, their life, etc. which isn’t always necessarily so in real life (because not everyone is self-aware enough to arrive at such poignant conclusions). It’s a theme, and Brown does well to show multifaceted motivations, but as a reader, I just got bored with it with this last set.

"Mistresses" makes some interesting craft moves with verb tense (past/present/future) jumps. Did you find this good for the story, or distracting?

It wasn’t just the tense jumps that I found distracting. It was also the sheer number of names that were introduced. I found myself going back over and over to remind myself who was who, and who had what relations with whom. Of all the pieces, I found this one the hardest to follow, simply because of the combination of tenses and names that I was required to keep track of. I’m sure that if I hadn’t been spending so much of my energy just keeping the characters straight, I would have been able to have a better appreciation for the craft manipulations Brown was attempting with the various tenses. I can see how it would give a fuller picture to Ivy and Jonah’s characters—jumping through time the way Brown does—so that their pivotal not-sexual encounter would be more impactful, but the names were just too busy for me to truly hone in on. I can see what Brown was trying to do, but I think it could have been executed better.